The Gridley Gold Fields Diary – “A MINER’S LIFE”

Daniel Ray / Toni Mann

PLACERVILLE, California (InEDC) Dec 22, 2022 — [1850, Chapter 2]

A MINER’S LIFE

The eastern sky is blushing red

The distant hill-top glowing

The brook is murmuring in its bed

In idle frolics flowing

‘Tis time the pickaxe and the spade

And iron “tom” were winging;

And with ourselves the mountain stream

A song of labor singing.

The mountain air is cool and fresh,

Unclouded skies bend o’er us,

Broad placers, rich in hidden gold,

Lie temptingly before us;

Then lifhtly ply the pick and spade

With sinews strong and lusty,

A golden “pile” is quickly made

Wherever claims are “dusty.”

We ask no magic Midas wand

Nor wizard-rod divining;

The pick-axe, spade and brawny hand

Are sorcerers in mining,

We toil for hard and yellow gold,

No bogus bank notes taking;

The bank, we trust, though growing old.

Will better pay by breaking.

There is no manlier life than ours,

A life amid the mountains,

Where from the hill-sides rich in gold,

Are welling sparkling fountains;

A mighty army of the hills,

Like some strong giant labors

To gather spoil by earnest toil,

And not by robbing neighbors.

When labor closes with the day,

To simple fare returning,

We gather in a merry group

Around the camp-fires burning;

The mountain sod our couch at night,

The stars shine bright above us;

We think of home and fall asleep

To dream of those who love us.

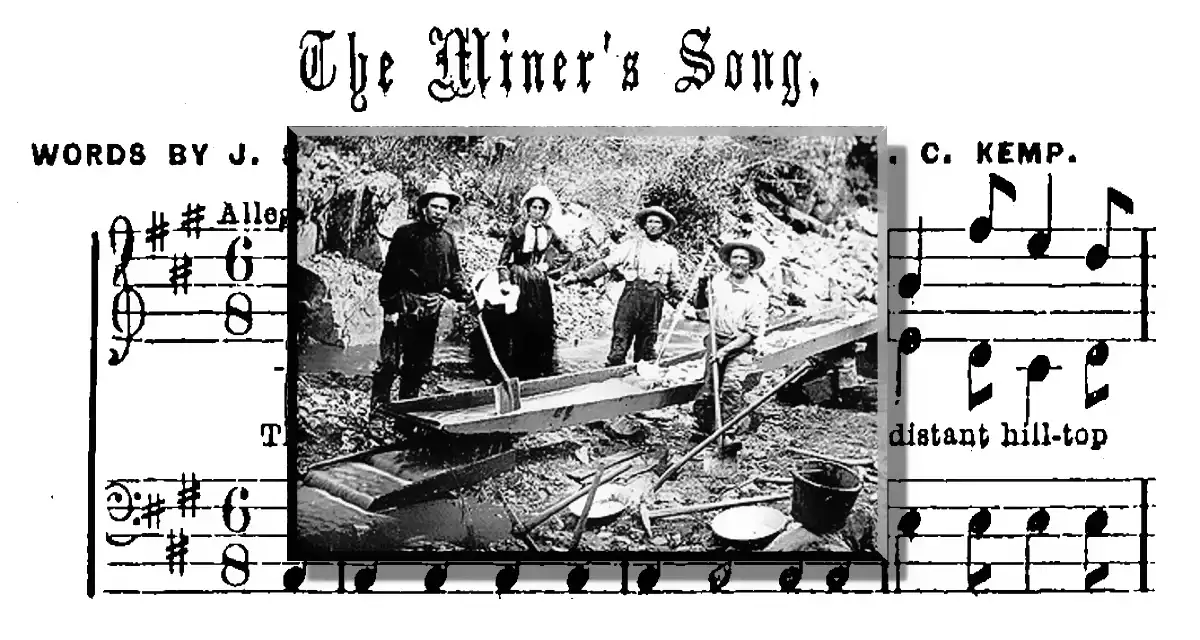

Song of Labor:The Miner by J. Swett (Paoli 1883)

John, George, and Charles Clingman stayed in Placerville for two or three days, camping with James Howard who had left Half Day for the mines in ’49. California, they were learning it was a big place. the mines numerous. and the information about them doubtful. The business of getting out the gold required more than just scooping up a fortune. Deadman’s Bar, Tuttletown, Coon Hollow, Columbia, Hornitos- where should they go co make their pile? North to the Yuba River or the wilds of the Klamath and the Trinity, or south to the Tuolumne and Calaveras where the Mexicans and Chileans were crowding … [page 14 missing]

Mining, they soon discovered, was not what they had expected back in Illinois. “People who have come to California this year,” wrote John. “find it altogether different than what they had pictured in their imaginations… .They have found a place where others have been before, made their fortunes, and left the gleanings for them. All the rich placers have either been worked out or are held by men who came in last year. There is scarcely a ravine, gulch, bar, or stream in California but what has been thoroughly prospected. Every place that will pay well which has not been worked out is crowded with miners, and thousands of men and traveling in every direction over the country hunting for places to dig. The miners here are making but three to eight dollars a day-small business indeed for those who expected to make a fortune of four or five thousand the first three months-(Gridley.10-14-50).

From 1850 to 1853, the Gridleys earned their livings primarily as miners, first at Dry Creek, and later at Carson Creek, Clarksville, and Mountain Home in El Dorado County.

The mines at Dry Creek and other diggings the Gridleys worked were placers – broad bars of sand and gravel where the streams, rushing from the Sierra Nevada, dropped the frag-ments of gold they had scoured from the mountains’ Mother Lode of quartz. The first requirement was to locate a claim by taking up abandoned diggings or buying out another miner, as the Gridleys probably did at Dry Creek and again on Carson Creek, or by prospecting on unworked streams. Prospecting was hard, dull work, scrambling up the tumbling foothill creeks, stopping at each likely bar-to wash samples of the dirt, searching the pan for the “color”, and, as likely as not, going home to the old claim at the end of the trip, out twenty or thirty dollars. It was no job for farmers and novices, but in 1852 and 1853 John and George prospected paying claims at Mountain Home and Carson Creek in El Dorado County.

Once a profitable spot had been located, a miner staked off a claim. Most mining camps allowed a miner no more than one or two claims of 1000 or 1500 square feet each, in order to prevent monopolies and allow each miner a chance at the diggings. Then the real work began. With pick and shovel, the too soil and the paying dirt were dug from the bar until bedrock or hard clay were reached. Ohce the dirt had been thrown up, the work of washing the gold from the sand and gravel could begin. In 1850, John, George and Clingman worked their claim at Dry Creek with a rocker or cradle, an oblong box about two feet wide and four feet long, divided in two by a stout hoard or iron bar. In one end of the box stood a hopper into which the dirt was shoveled. Then, with water carried from the creek, the dirt was washed down across the series of cleats and riffles in the lower end of the box. By rocking the cradle, the sand and dirt could he broken up and kept in constant motion. carried by the water down and around the riffles where the heavier gold would fall from the stream. Frequently mercury was placed in the lower riffles where it attracted and held the fine particles of gold dust.

By spring of 1851, John, George and Clingman bought better equipment, including a “tom”, a box much like the lower end of their cradle, but up to fourteen feet long with many more riffles to •catch even the finest gold before it washed from the lower end. The new technology required more men and water to work, so they took two other men into the operation, and paid each miner a sixth of its daily yield, with the last sixth split between the original partners as the owners of the tem. To supply the extra water that the long tom required, they bought hose and a pump, a Yruck Silver Machine, for 200 dollars. The pump was apparently less than reliable. When John was asked why he never sold it, he admitted he hadn’t the impudence to offer it to anyone.

The Gridleys mined mostly at “dry diggings”, small creeks and gulches which depended on ephemeral streams and California’s winter rain for water. When they arrived at Dry Creek in 1850 they reported that “the creek is now nearly dry so that the bars and bed of the stream can be worked. After the rain commences these will have to be abandoned, and mining operations confined to the banks of streams and ravines which are now dry ” (Gridley.l0-14-50).

In 1852, John wrote from Mountain Home that “George and his partner, Tucker. threw up considerable dirt in a very short ravine near here which pays very well, but the water runs off so quick that they cannot wash much, only when it rains. George and Tucker worked all the while it rained, washed out over two hundred dollars ” (Gridley.1-2-52). Later at Clarksville, George reported, ‘The winter has been dry and mild. Water for mining is scarce. The last three days have been rainy. The miners about here have been rusticating in various ways for the last month. but are now at work, making from four to eight dollars per day “(Gridley. 10-1-56). By the mid – L850’s, the new water companies were building canals to supply dry diggings such as the Gridley’s claim on Carson Creek, making year round operations possible. In the early years, many miners moved in the summer to river diggings such as the American or Mokelumne, where water was always available to work the broad river bars, and companies of men might divert the stream with wing dams and contain it entirely in a sluice to work the river bed. John Gridley hoped to join in a sluicing operation with old friends from Half Day, the Roses and Mr. Clock, a neighbor from Indian Creek, on Clock’s claim near Georgetown in El Dorado County, but the diggings were all claimed and they could not get in. By 1851, miners were also learning more about the gold country’s geology, and began to look up from their placers to the gold studded quartz veins of the Mother Lode itself. On a trip to Placerville, George found “tunneling all the rage”. He went into a mineshaft to watch the hard rock miners working with pick and drill by candle light, found it “quite a curiosity”. He bought two shares of stock in the company, and went back to the dry diggings.

For any miner, the highlight of the days labor came when the pump lay quiet, the picks set amide. and the fine particles of gold, mixed in an amalgam with the mercury, were carefully washed from the rocker or tom. There is an excitement in gold digging”, wrote another miner, “which [ends to reconcile one to hard work, as he looks forward to the washdown at the end of each run with interest; moreover, the few minutes relaxation afforded by the process is a period of comparative rest. A miner soon learns to judge by the clean up at the end of the run how his dirt is paying, and can tell pretty near what will be the result of his days work ( Gardiner 1970). In the evening, after a final cleaning in the miner’s pan. The amalgam was heated. next to dinner. on the stove, driving the mercury away in a vapor and leaving the days pay. For John and George. that meant five to ten dollars on most days et Dry Creek. Later, at Mountain Home, John and his partner Tucker Dry Creek. Later, at Mountain Home, John and his partner Tucker made thirty dollars apiece for five days running. Some claims nearby paid twenty five to two hundred dollars to the man per day, and several Dry Creek claims yielded fortunes of ten to twenty thousand dollars. Large nuggets were found occasionally. George found one worth twenty four dollars on Carman Creek in 1851, and the next year a boy cleaning up behind John and Tucker took out a piece worth sixty dollars. At other times. good prospects failed to “pan out”. At Dry Creek, unexpected high water forced them out of a good claim in early November, 1850. In the winter of 1851, John. George, and Tucker threw up 15.00 to 20.00 buckets of dirt which prospected at floe cents to five dollars a pan. Around the table at the Mountain House, they began to calculate their honed for pile – 2000, 3000, maybe even ‘000 dollars. But in December, the rains did not come, and in January the lack of water kept the dry diggings at a standstill. “The great drouth Is ruinous to the gold crop,” George wrote. By the end of February. only 8 1/2 inches of rain had fallen compared to 32 inches in 1850. With the little water they had, they washed only 1000 dollars from the claim. The drench was the worst of the century. Along the small creeks and gulches, disappointed miners abandoned their claims or sold them “dirt cheap”. On other creeks they met miners who “drank more than they washed and thought the work) too hard for them. I suppose there are no many returning from this country minus the ore,” wrote John. “that you begin to suspect that fortune seeking here is as uncertain as it is elsewhere. Of all that came here from our vicinity few have made enough to pay for the coming and none have made much of ELL!. but whether the fault is in the country, or in the men, Is not quite decided. Those who work steady can make from four to eight dollars a day sure, with a chance of making a pile. New discoveries are continually being made and must . be for ages.[In the other hand), this is as good a country as any to lose money in. We have paid out nearly all our money in mining operations which is the same as the game of chance (Gridley. swig.. letters).

While the pay was erratic, a miner’s life was simple and his needs few. ‘Ills clothing,” wrote George, “will cost him less than in the States. as fashion does not demand a twenty dollar coat. He wants only a pair of woolen shirts, three or five dollar pants. boots, a hat, and a blanket or shawl to throw over his shoulders.” Food was expensive, but by 1851, had fallen to half its cost the previous year. The Gridleys’ Larder at their first winter camp at Dry Creek included pickled pork, cheese, potatoes, pickles, raisins, and honey. Like many miners, they kept small gardens in which grew turnips, beets, tomatoes, watermelons, beans and “all kinds of garden sauce”. Pies could be baked with dried apples, sugar and the flour they bought by the hundred weight. Pancakes and sourdough bread were made by substituting saleratus for yeast. Quail could be purchased from the local Indians and pigs and beef from merchants in town. Despite the high prices, George reported, eggs still came twelve to the dozen. “Pa wished we had some of his good dinners,” he wrote “Well, we do too. I do not like to cook well enough to have any extra doings, but we do have good bread, potatoes, onions, squashes, ham, bacon, eggs, tea, coffee, sugar and butter, except when we had rather do without than go to the city after it. I am sorry to say that our table cannot boast tonight of as many luxuries as it could a week ago, for our jar of butter is gone. It was first rate – 75 cents a pound. Our honey is out too. Our living is not such as we used to get at home, of course, but most of the time we have what we want to cook of the substantials. We have a good time here, no care on our minds, only when its cooking day ” (Gridley.various letters).

— To Be Continued —

Prolog: The Miners

Chapter 1, Part 1: – Gone to See the Elephant!

Chapter 1, Part 2: – The 40-Mile Desert, a Barrier Without Water

Chapter 2, Part 1: – “A Miner’s Life”

[Transcribed from original handwritten letters mailed home from “the diggins,” between 1850-1859. George Gridley, aged 29 and brother John T. Gridley, age 21]