The Gridley Gold Fields Diary – Gone to See the Elephant!

Daniel Ray / Toni Mann

[The following pages were transcribed from original handwritten letters mailed home from “the diggins,” between 1850-1859. George Gridley, aged 29 and brother John T. Gridley, age 21]

PLACERVILLE, California (InEDC) Dec 20, 2022 —

PART 1

Oh, surely we are seeing the elephant, from the tip of his trunk to the end of his tail! – Lucy Cooke

In 1849 and 1850, the gold fields of California were the talk of the whole country and half the world. In the streets and on the wharves of New York and New England, on the farms of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, in Europe, South America. and China, men exchanged stories about El Dorado, “a land so rich in gold that they had but to stoop to pick up a fortune, where gold was so plenty that it was impossible to miss it” (Gridley.10-14-51). At Long Grove, our great-great uncle John Gridley just turned 19, heard the news and thought of joining the argonauts’ rush.

George Fenwick, from Diamond Lake, J. Howard, the Sutherlands, Elijah Hubbard and others from Half Day were already makil, plans to go. Perhaps he remembered his excitement as a five year old boy pioneering newly opened Illinois with his father and brothers in 1835. No doubt others in the family remembered their early days in Lake County as well – the disease, lonlincss, hardships’, and uncertain conditions. California was no place to send a boy of 19 alone his father said. They held him home until 1850, and then, according to Grandad, “elected. his brother George, our great grandfather, eight years his senior, to accompany him.

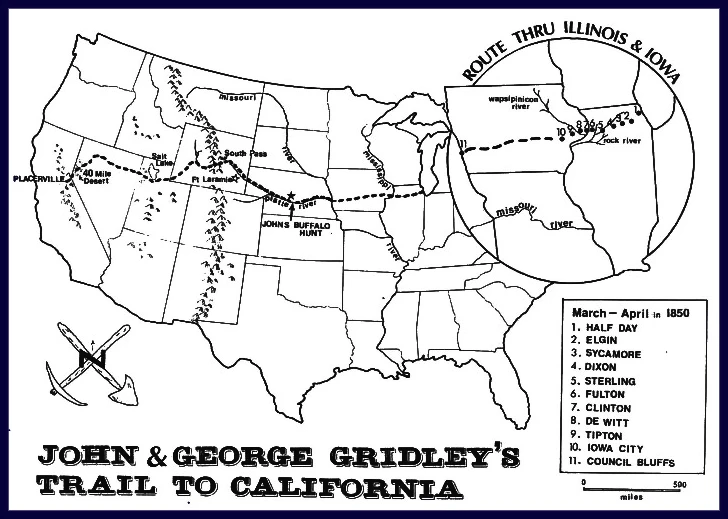

They left in early March, 1850. Their party included other Lake County men – Charles Clingman, from a Long Grove farm just south of theirs. Mr. K. Kieffcrs, old Mr. I.rmebeck, Mr. Parsons, Behrisch, and Cal Rose and his brothers, their neighbors on the Port Clinton Road. They took 8 horses which pulled a wagon loaded down with their tent, stove, provisions, and feed for the horses. George left his favorite saddle horse. Sam. at home. They were “bound to see the elephant”, and promised their brother,Elisha, that “when we get sight of him we will let you know how he looks.”

On Sunday, March 24th, they were joined at Samonauk by Chancy Hoffman (perhaps from a Des Plaines River farm north of Half Day). The company moved west through Illinois on a route that parallels today’s Interstate 80, keeping an eye on prospective farmland for Elisha, first through “excellent country, the prairies large, but interspersed with Pine groves of timber”, through Shabnees Grove, PawPaw Grove, Mulligan’s Grove, Inlet and Kennebee, traveling with three other wagons bound for California. At Dixon they ferried the Rock River and pushed through Sterling, Como and Unionville, past land “sandy, sterile, thinly settled and poorly cultivated.” At Fulton they paid two dollars to the ferryman for passage across the Mississippi, and rolled west into Iowa, it more thinly settled state than Illinois, its roads sometimes bad, with many small streams to cross. The prairies were “wet and rotten”, and timber and water were scarce. They passed through Clinton County, crossed the Wapsipinicon, pushed on through Stott County, and headed for Its City, traveling about 20 miles it day, the men walking along beside the wagon most of the time. They bought their meals and boarded in houses when they could. but as they approached the main trails west, settlers homes became fewer, travelers more numerous, and they slept in the wagon more frequently. The road was crowded with teams.

John reported that:

Every road. tavern, and place where it is possible for man or beast to stay is literally thronged with the gold hunters. The emigration through here is immense. The Californians have drained the country of nearly all the by and grain there is in it; and without the country beyond here is better supported with provender than this, I don’t know but we will have to wait for grass before we reach Council Bluffs (Gridley.3-31-50).

Already grain cost 6C per cent more than it had in Illinois. Their travelling costs, excluding lodging and meals, rose from 8 1/2 cents to 14 cents a mile. And every day the road was more crowded. On March 31st they shared their campground at Mariner’s Grove with fourteen other persons They reached Council Bluffs, the main trailhead for California emigrants from the Lake states, in mid April. Here they bought another horse and probably grain and other supplies brought up the Missouri River by steamboat from St. Louis. They checked for letters from home, but none had arrived.

Somewhere to the west, 2500 miles away, by California Between Council Bluffs and the gold fields was a country whose likes they had never seen. Instead of the deep soils and tall grass prairies, the winding wooded creeks and oak groves of Illinois, they looked from Council Bluffs on a treeless plain where the grass on the sandhills barely reached a man’s calf in July, without shade from the sun, where the only water was in fetid and muddy river bottoms or musty wells dug into swampy drainages. Traveling became more difficult. As John said, “traveling 30 miles a day, walking two thirds of the time, taking care of the team, and being on guard nights is anything but easy.” Still they were “a11 well with the exception of some bad colds, all in good spirits, strong in the faith, determined to persevere, press on, and, if possible, search the ‘promised land of gold” (Gridley. 3-31-50).

On the Platte River,John tried his hand at buffalo hunting, and concluded that the business was a little big for me..

One morning when we were in the buffalo range about 200 miles up the Platte,I left camp in the company of four or five others and set out upon a hunt. It is not like hunting deer or other game at home. There the first thing is to find them, but here the difficulty is in killing. Ott left the road which winds along the river bottom and went out among the sand bluffs to the north. Here I saw a sight which was beyond anything I had ever seen in the line of stock. Every hollow and ravine, far as eye could reach, was a living, moving mass of buffalo meat. It was no trouble to get within close shooting distance, but our bolts seemed to have no other effect than to make them shake their heads, lift their tails, and run in with the herd. After chasing them nearly all the forenoon over the hills of sand and wounding many of them, we succeeded in hitting a large bull in a vital part and brought him down. Each one took as much meat as could conveniently be carried and started to overtake the teams. After chasing them nearly all the forenoon over the hills of sand and wounding many of them, we succeeded in hitting a large bull in a vital part and brought his down. Each one took as much meat as could conveniently be carried and started to overtake the teams. After walking as rapidly as we could for three miles through the sand, we came to the river bottom which was here four or five miles wide and covered with a heavy growth of grass We took an oblique course across the flat so as to intercept the teams at a point where we thought it would be likely to wait at noon, but we had to run around sloughs, wade creeks, tramp through the tangled grass and shoot at wolves (the large kind- very numerous) and did not reach the teams until 2 or 3 o’clock. It was the hardest day’s work I ever done (Gridley.11-25-50).

The meat, he reported, was “about as fat and tender as old Van Buren’s 1 would be after running all winter to grass.. As evening approached, the wagons would be drawn up, and while some drove the horses out to pasture, others among the men would gather firewood or buffalo chips and prepare dinner. “We foot it most of the time,. John noted, “and have the very best of appetites. (Gridley.3-31-50). And then around the campfires at night, another 49er reported, the sound of a violin, clarionet, banjo, tamborine or bugle would frequently be heard, merrily chasing off the the weariness and toil of the travelers, who sometimes ‘tripped the light fantastic toe’ with as much hilarity and glee, as if they had been in a luxurious ballroom at home” (Delano.1854).

Disease stalked the emigration of 1850. Bad food and water, coupled with the weather and their daily toil, left men poorly prepared for the epidemics of cholera and Rocky Mountain fever that ran through the trains in Nebraska and Wyoming. George fell ill with cholera along the Platte and John, Mr. Parson, old Mr. Limebeck and Charles Clingman struggled with mountain fever from South Pass to Salt Lake City. Tie road west was literally lined with the graves of those who did not survive to write letters home about their trip.

Once on the trail, the emigrants were beyond the reach of any law, and had to rely on their own wits and what feeling of civilization they were able to bring from the East.

1 presumably an ox or bull on Elisha’s farm.

After long days of endless labor, a moment of tension or an unexpected incident could cost a traveler his stock, his wagon, or his life. The ability to measure one’s traveling compan-ions, who might be casual acquaintances from home or the trail, and to enlist partner’s with common sense and cool heads was as important a skill as abilities with stock or in the out-of-doors. Somewhere along the route to Salt Lake City, perhaps near Fort Laramie or along the Sweetwater. John and George found themselves embroiled in “the pony scrape”. A traders pony, loaded with poles and skins, came down the trail towards the spot where the horses were grazing after a long day in the harness. The sight of the odd beast and the strange sound the poles made dragging on the ground was enough to spook the weary teams . With their tails in the air, they ran for hills. The pony bolted and ran after them. The men had to think quickly. Without their stock they would be stranded, 1200 miles from either home or California. L. Dana and Hartnett, two men they met on the trail, drew their pistols and shot the pony. Once the horses were collected, Parsons suggested that it would be prudence. to pay the trader for the dead pony, and recommenced that George go to make the settlement. Hartnett volunteered to go along too, but instead. according to George, “left the camp and went I don’t know where. There is no blame attached to anyone on my part. It naturally wanted a little gas just then to lighten the ‘darkness of the scenery.” (Gridley.9-8-51).

Still, tempers remained short. Oct June 19th they arrived at Salt Lake City. They probably purchased more supplies, and then, on a Sunday morning, Parsons left with Lathrop, “much to the satisfaction of all. ;Gridley .11-25-50. On June 25th, the others pushed on towards the Humboldt River and Nevada. Men used to living in fertile land like Illinois, said a 49er,

Can form no correct idea of this feral, dreary waste. To travel month after month without seeing anything worthy of the name tree and the moment you leave a stream, no grass, and [even along the streams] you seldom see good grass. I have not seen any rain for several weeks and but little then. It is most wonderful how these bodies of sand were brought together, hills of sand and plains of sand. The roads are very heavy and sandy. The sand is from the to six inches deep. The road is as dry as ashes. Dust like fog (Scamehorn.1965).

Still, they pushed west and made the best of it. Crossing the Salt Lake Valley and on the trail along the Humboldt River in mid-July, they had, John admitted, “some rather warm days” (Gridley.11-25-50). Their horses began to weaken and they must have begun to think of abandoning their wagon and joining the emigrants who were crossing the desert on the sore backs of horses and oxen, or on foot. By the summer of 1850, according to an emigrant of 1849:

The grass was dried up in many places where we found it good, and the melting snows rendered the streams so high, that they were crossed with difficulty. The lower valley of the Humboldt where we found a smooth level road the previous seasons. was. . .in 1850 overflowed, presenting one vast lake and the emigrants were compelled frequently to keep to the hills or uplands, either in deep sands, or among rocks and ravines, with their worn-out animals, while the overflowed valley afforded no grass. Long and laborious detours were necessary, to avoid flooded lateral valleys, under water. . ..In traveling down that river, grass was obtained frequently only by wading or swimming to islands and cutting it with a knife (Delano. 1854).

— To Be Continued —

Prolog: The Miners

Chapter 1, Part 1: – Gone to See the Elephant!

Chapter 1, Part 2: – The 40-Mile Desert, a Barrier Without Water

[Transcribed from original handwritten letters mailed home from “the diggins,” between 1850-1859. George Gridley, aged 29 and brother John T. Gridley, age 21]