The Future of Okei’s Gravestone

(by Herb Tanimoto)

PLACERVILLE, CA (May 10, 2022) American River Conservancy is seeking public opinions about the future of Okei’s original gravestone.

Every immigrant group coming to American shores faced tremendous obstacles in achieving their dreams of success. The Japanese immigrant story is no exception. Many began coming after the labor shortage caused by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Soon Japanese immigrants found prejudice extended to them with the passage of alien land laws and the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924, which were not rescinded until the 1950s. Then after WW2, a dark chapter in American history played out when approximately 120,000 innocent Japanese American citizens lost their homes, possessions, and much more in internment camps. With hard work, especially in agriculture, the Japanese were nonetheless able to rebuild and thrive within American society.

In their quest to find cultural identity in America, many early Japanese immigrants were astounded to learn of the discovery of the grave of a Japanese girl named Okei hidden in a thicket of brush and trees in the Sierra foothills. Amazingly she had preceded most of them by 30 to 40 years! But who was she? What hardships did the young girl face as one of the first Japanese immigrants?

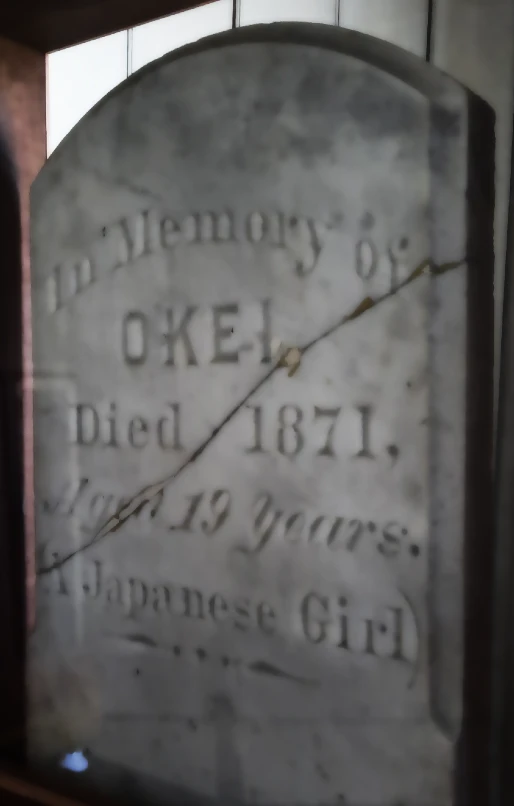

The discovery of her gravestone revealed a previously unknown story about the first group of Japanese settlers in America who started a tea and silk farm near Coloma in the gold fields of California. Back in 1869, they were refugees from a civil war. Their dreams of success ultimately vanished when arid summer conditions killed their thousands of tea plants, the lifeblood of their farm. Their Prussian honorary samurai leader, John Henry Schnell, abandoned them as the colony disbanded within two years.

Of the original 22 colonists, few remained in America. Among them were Okei and her friend, Matsunosuke Sakurai. They became part of the neighboring Veerkamp farming family who subsequently purchased the former Colony site. Perhaps Okei longed to return to Japan, but it was unlikely she had the funds to return home. By 1871, she had contracted a deadly fever. At the age of only nineteen, her untimely death made her the first Japanese woman and immigrant who died and became buried on American soil.

The Veerkamps arranged her burial on the knoll where she often sat and gazed longingly in the direction of her homeland. In an act of tremendous kindness, Matsunosuke saved funds for some 15 years to purchase a lasting marble marker for her grave. It was carefully placed so the Japanese lettering faced west toward Aizu Wakamatsu, Okei’s homeland; and the English lettering faced inland America, the country where she still rests in peace today.

Okei’s gravestone stood for more than 100 years before it was severely damaged sometime after the Japanese American centennial celebration at the Farm in 1969. Somehow the crack was repaired. By the time American River Conservancy (ARC) bought the property from the Veerkamps in 2010, the stone could no longer safely remain exposed to the elements. ARC arranged for an exact replica, and the original was moved to a secure location. Another replica of the headstone exists atop Mount Seaburi at a memorial site in Aizu Wakamatsu, Japan.

Okei’s life story is symbolic of the many thousands of Japanese who have followed in her footsteps arriving in a foreign land with little more than hopes and dreams. Ultimately, Japanese Americans have made immense contributions to the American economy and culture. Meanwhile, Okei’s grave has become a pilgrimage site for generations of Japanese Americans and Japanese people touched by her story of perseverance and sacrifice in the face of an unknown fate. Her original gravestone is not only the testament of her life. It is the very reason why the Wakamatsu Colony story remains alive today. Her gravestone is also a symbol of the importance of honor and duty, the samurai values of Matsunosuke’s world. That he would honor his friend so beautifully by giving her this lasting memorial is touching beyond words.

A unique artifact of such significance deserves a place of prominence and protection. Returning it to the outdoor elements would expedite its demise. A world-class museum is not within scope of the Conservancy’s long-term plans for Wakamatsu Farm. As a land trust with over 33 years in environmental conservation and stewardship, artifact preservation is beyond the Conservancy’s core mission. The place where the stone is now modestly displayed at the Farm is not readily accessible to the public and particularly non-accessible to disabled visitors. Perhaps gifting the priceless artifact to a museum or other qualified artifact repository is the most prudent choice for posterity. Public display in a place where more people will discover the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony story would likely result in many positive outcomes, not only for Wakamatsu Farm, but also for the preservation and telling of American history. Yet, moving the stone from its place of origin is no simple choice.

At this time, American River Conservancy is at a decision point about the fate of the precious item. In the spirit of a community dialog, the Conservancy is reaching out to interested individuals and organizations to determine what course of action will best serve the gravestone’s perpetual preservation. With the goal of building stronger ties to Wakamatsu Farm, American River Conservancy remains committed to sharing the story of Okei, Matsunosuke, the pioneers of the Wakamatsu Colony, and the enduring legacy of Japanese American immigrants through shared connections to the land where it all began.

To participate in the community dialog about the future of Okei’s gravestone, please email wakamatsu@ARConservancy.org or call 530-621-1224.